The legacy of coal is important in understanding the future of Appalachia. Coal taken from West Virginian (and other Appalachian) mountains almost literally powered building the industrialized United States. While mines were operational, miners largely earned living wages, joined strong unions, and achieved a middle class life. However, coal today makes up a far smaller portion of American energy consumption than 50 years ago, and many of the geographic areas producing coal are now poverty-stricken and suffering from public health crises ranging from opioids to smoking to obesity. In thinking about why this is the case, it is important to keep a few facts in mind:

Most coal mines were located far from established towns, which led miners and mining companies to build towns in more convenient locations. These included cheap homes, a company store, and a church. Rather than bringing the banking system to the miners, mining companies generally paid miners in “coal scrip,” a simplified system in which miners could exchange the scrip tokens for goods at the company store. Though convenient at the time, this system created generations of miners and families that lacked financial literacy and were excluded from the modern financial system.

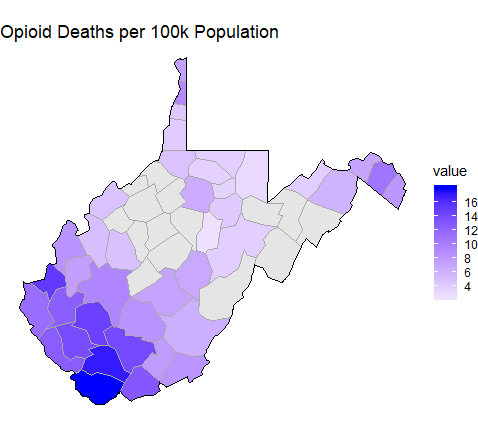

Coal mining is hard. Ranging from respiratory problems (e.g., black lung) to chronic pain, there is no doubt that miners themselves paid a physical price of walking into mines every day. But coal by itself does not explain the opioid crisis. While true that there is evidence that substandard working conditions can lead to addiction, and over-prescription of opioids should not be overlooked, a more comprehensive view leads to a “disease of despair” explanation for the West Virginia opioid crisis. So we should think about education, obesity, and poverty (to name a few) as part of a system that creates economic and social disadvantage that helps explain the severity of the problems in West Virginia.

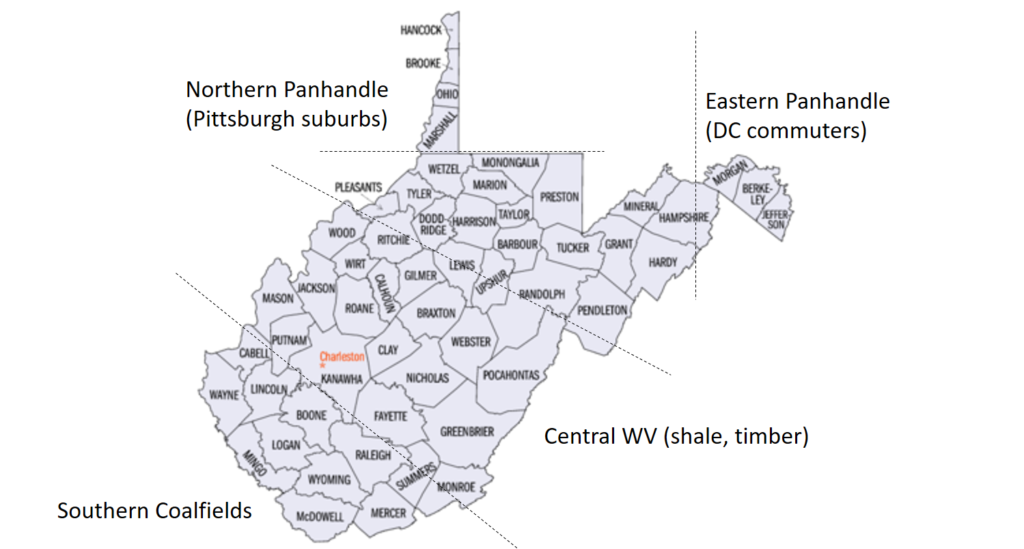

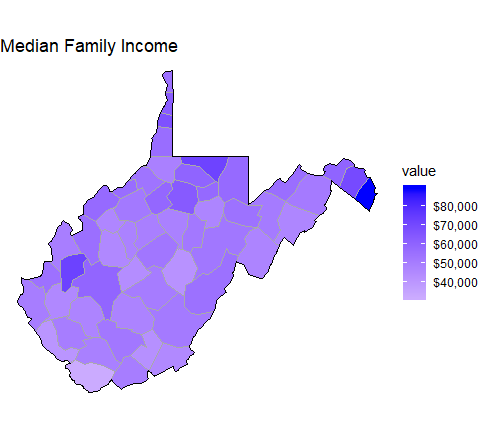

Regional differences in West Virginia are important. Coal production in Southern West Virginia decreased approximately 70% (from 130 million tons to 40 million tons) between 2000 and 2017. Yet for Northern West Virginia, production actually modestly increased from just under 40 million tons in 2000 to just over 40 million tons in 2017. To explain this, we can note a few important factors: first, to the extent there is other industry in West Virginia, it is located in the Northern part of the state (primarily logging and shale gas mining). Second, the Northern West Virginia is geographically less remote than the Southern part: the “Eastern Panhandle” arguably benefits from Washington D.C. spillover effects and the “Northern Panhandle” includes suburbs of Pittsburgh (commuters drive for less than an hour). These regional differences manifest in demographic and public health statistics: Southern West Virginia shows worse public health outcomes, has lower median HHI, and lower life expectancy than Northern West Virginia.

West Virginia has historically not invested in public education. Despite modest gains based on the successful 2018 teacher strike that resulted in a 5% raise (and catalyzed teacher strikes in numerous other states), West Virginia remains significantly behind on public education. West Virginia ranks last in percent of population with a bachelor’s degree (a shade under 20%) and 49th in percent of population with an advanced degree (7.9%). West Virginia teachers went on strike again in 2019 protesting a state bill privatizing public education despite the fact that if passed teachers would have gained an additional 5% raise. Structurally, this investment stems at least partially from the lack of education necessary for coal mining jobs: historically, many West Virginians sacrificed formal education to enter the mines.

As an employer, coal has not been replaced. Today, Wal-Mart is the state’s second largest private employer, Kroger the fourth, and Lowe’s the seventh. The rest of the top ten include five hospitals, Mylan pharmaceuticals (generic drug-maker), and Res-Care (Kentucky-based company providing in-home services to people with disabilities). Notably, there is not a single energy company on this list. It is hard to find longitudinal employment statistics, but just since 2005, coal industry employment has dropped approximately 30%. The number since the height of coal production (e.g., 1950) would almost certainly be far more staggering. It is also important to note that West Virginia is not the only state impacted by the decline of coal: of the top ten coal-mining companies in the US ranked by production per year in 2014, the first, second, fourth, and seventh (representing 44.2% of total 2014 coal production) were bankrupt by 2018.

State government has historically promoted pro-business policies that helped coal companies thrive. Specifically with regards to environmental protections, West Virginia has been on the forefront of deregulation. Though a cherry-picked example, it is almost unbelievable that weeks after a chemical spill at a coal refining plant spilled 10,000 gallons of chemicals into the Elk River leaving ~300,000 people without potable water, Democratic governor Earl Ray Tomblin warned the Obama EPA of “unreasonable” protections.